Opinion

Somaliland Is Not Somalia

Somaliland, located in the Horn of Africa, has declared its independence from United Kingdom on 26 Jun 1960, Somaliland is a neighbor of Somalia, a state often marred by political instability and conflict. This article seeks to articulate the historical context surrounding Somaliland’s quest for independence, highlighting the differences between Somaliland and Somalia, and arguing for the recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state.

Historical Context of Somaliland and Somalia

Somalia’s journey to independence is often celebrated on July 1, 1960, the day it emerged as a unified republic from colonial rule. However, a critical examination reveals that this independence was not a unilateral achievement but rather a culmination of earlier political developments. On 26 June 1960, Somaliland became an independent and sovereign stat and Restoration of sovereignty 18 May 1991. Just five days later, on July 1, that newly independent Somaliland was merged with the southern regions, formerly under Italian administration.

This transition from being a British protectorate to joining Southern Somalia was not the seamless union often portrayed. The political machinations of the time obscured the distinct identities and aspirations of the regions involved. In fact, Somaliland’s independence predates Somalia’s by five days, raising essential questions about the legitimacy of Somalia’s claim to ownership over the notion of Somali unity.

UN Membership and the Legitimacy Debate

Upon gaining independence on July 1, Somalia quickly sought membership in the United Nations, with its application formally submitted under the name “Republic of Somalia.” This was supported by resolutions from the United Nations General Assembly, notably Resolution A/RES/1479(XV) on September 20, 1960, granting Somalia full UN membership.

However, the legitimacy of this membership is contested by proponents of Somaliland’s independence. They argue that Somalia’s claims to independence and UN membership do not include or reflect Somaliland’s status. The foundational documents and international resolutions reveal that while Somalia was granted independence, it did not obtain it in a manner that negated Somaliland’s prior sovereignty.

The Distinct Identity of Somaliland

Somaliland has established a governmental structure, a distinct identity, and a functioning economy since declaring back its independence from Somalia in 1991, following the collapse of the Somali central government. Unlike Somalia, which has struggled with civil war, terrorism, and political disarray, Somaliland enjoys relative peace and stability. This reality has fostered a sense of national identity among Somalilanders that stands apart from the chaos in Somalia.

The Modern Reality of Somaliland

While Somaliland operates as a independent state, it lacks formal recognition from the international community. This absence of recognition stifles its political and economic potential, limiting access to international financial institutions and aid. Nevertheless, Somaliland continues to build its institutions and develop its economy, striving for the legitimacy that comes with international recognition.

The argument for recognizing Somaliland is bolstered by its peaceful governance, structured legal system, and commitment to democratic principles, as evidenced by its regular elections. These characteristics starkly contrast with the ongoing turmoil in Somalia, reinforcing the notion that Somaliland functions effectively as a separate country.

The Legal Perspective on Celibacy and Recognition

The debate surrounding Somaliland’s status hinges on legal perceptions of statehood and independence. While Somalia claims a historical union based on post-independence transitions, it is crucial to recognize that Somaliland’s prior independence on June 26, 1960, creates a different narrative. The argument for shared independence lacks legal validity, as these regions were two distinct political entities before their temporary union.

Moreover, Somaliland maintains that its struggle for recognition is not a call to irrevocably sever ties with Somalia, but rather a quest for acknowledgment of its unique sovereignty. This perspective aligns with international norms regarding self-determination and the rights of peoples to govern themselves.

Conclusion

The case for Somaliland’s independence rests on historical context, legal arguments, and the contrasting realities of governance compared to Somalia. Recognizing Somaliland as an independent state is not merely an act of political support; it is an acknowledgment of historical truths and the assertion of the rights of its people to self-determination. As the international community reassesses its stance on Somaliland, it must consider the historical injustices and the current realities that distinguish Somaliland from Somalia.

The world must recognize that Somaliland is not Somalia, and it deserves its rightful place on the global stage.

BY; Abdullahi Ahmed Heef

How Somaliland’s Quest for International Status Challenges Existing Norms and Agreements

Advice to the Government of Somaliland Regarding International Relations and Security

Opinion

From British Ally to Israeli Partner? Examining a Century of Somaliland’s Foreign Relations

Analysis of Somaliland’s historical military alliance with Britain and its contemporary alignment with Israel.

This report examines the proverbial claim that history is repeating itself with Somaliland, comparing its historical participation alongside British forces a century ago with its current burgeoning relationship with the State of Israel.

The available evidence confirms that the territory of Somaliland was indeed a theatre of conflict during the early 20th century, particularly during the Somaliland Campaign (1900-1920). During the First World War, the British Somaliland protectorate was aligned with the Allied powers, and Somaliland troops, notably the Somaliland Camel Corps, fought alongside British forces .

In a significant contemporary parallel, Israel became the first country to recognise Somaliland as an independent state in December 2025. This has been followed by high-level diplomatic meetings and a visit by Israel’s Foreign Minister to Hargeisa in January 2026 . While Somaliland fought alongside Britain as part of a colonial protectorate, its current alignment with Israel is a diplomatic and strategic partnership between two sovereign entities, driven by shared geopolitical interests in the Red Sea region. The parallel is therefore not an exact military one, but a recurrence of Somaliland forging a critical alliance with a major power to ensure its security and pursue international recognition.

Historical Context: Somaliland and the First World War:

During World War I, the territory that is now Somaliland was a British protectorate. While the global conflict raged in Europe, the region was embroiled in its own prolonged conflict, the Somaliland Campaign (1900-1920)*, also known as the Dervish War . This campaign pitted British forces against the Dervish movement, led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan.

Although the Dervishes received some support from the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with Germany, the British somaliland protectorate forces remained loyal to the Crown .

Somaliland Participation in the Allied Effort

The local population was not a passive bystander. The British established the Somaliland Camel Corps, a unit that took advantage of local Somaliland skills to fight in the harsh terrain . This corps saw action both in the Horn of Africa and in other theatres like the Far East.

A Proud Heritage: For many in the Somaliland diaspora today, the service of their grandparents in the First and Second World War is a source of pride and a part of British history. An exhibition titled Somaliland People and the First World War” was created to share these memories and highlight the contribution of Somaliland soldiers to the Allied cause .

It is important to note that the conflict was complex. While some Somaliland fought with the British, others joined the Dervish resistance against British, Ethiopian, and Italian colonial rule .

Historical Parallel: The first “repeat” in history is Somaliland’s role as a strategic ally to a global power, contributing to its security framework in exchange for protection and political support.

Contemporary Context: The Alignment with Israel:

A century later, Somaliland has made a significant geopolitical move by forging ties with Israel. In December 2025, Israel became the first nation to formally recognise the Republic of Somaliland, which has been a self-governing but unrecognised state since restoring independence in 1991 .

This recognition has been followed by rapid diplomatic engagement; high-level Meetings; Somaliland’s President, Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (known as Irro), met with Israeli President Isaac Herzog and Eric Trump at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2026 to discuss bilateral relations and investment . It was also a historic visit where Israel’s Foreign Minister, Gideon Saar, visited Hargeisa in January 2026, marking the first official visit since recognition. He met with President Abdullahi to advance political and strategic partnerships .

The alliance is driven by clear strategic interests for both parties; For Somaliland, recognition is the ultimate goal. However, Israel’s move is a major breakthrough in its decades-long quest for sovereignty. President Abdullahi has stated Somaliland would join the Abraham Accords, and the government is pivoting from asking for aid to offering investment opportunities, particularly in the strategic Port of Berbera.

For Israel, the Horn of Africa is a critical strategic theater. Analysts suggest the driving force is the need for allies in the Red Sea region to counter the Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen, who have threatened shipping lanes and fired on Israel. An increased Israeli footprint in Somaliland could help with intelligence and deterring weapons smuggling .

Analysis: History Repeating or a New Paradigm?

The parallels are striking but not identical. The “repeat” lies in Somaliland’s consistent strategic orientation towards powerful extra-regional actors to secure its interests.

In the first instance, it was as a British protectorate, with its people fighting as loyal subjects within the Empire’s forces.

In the current instance, it is as a self-governing entity seeking the ultimate prize of statehood. The alliance with Israel is a diplomatic and economic partnership, not be considered as a military one commanded by a colonial power but the chances of both forces fighting with terrorists in the sea and the read sea is eminent . While security cooperation is likely a component, Somaliland is also negotiating as an independent actor.

The notion that “history is repeating itself” holds validity when viewed through the lens of Somaliland’s geopolitical strategy. A century ago, the territory aligned with the British Empire, contributing troops to its campaigns. Today, Somaliland has aligned with the State of Israel in a landmark diplomatic and military move.

While the context has shifted from colonial military service to modern sovereign diplomacy, the core theme remains: Somaliland continues to forge critical alliances with global powers to navigate a challenging regional environment and secure its future. The current partnership with Israel, born out of shared interests in Red Sea security and the pursuit of international legitimacy, represents a new chapter in this long-standing historical pattern.

Mo Saeed

Somaliland Legal Research

Opinion

The Unfinished Genocide: A Strategy Repeated

Mapping the Perpetual Threat: Foreign Intervention and the Siege of Somaliland’s Sovereignty.

By Mo Saeed

Introduction:

This report examines two distinct but thematically linked allegations concerning external military intervention in Somaliland. The first is a well-documented historical case: the hiring of foreign mercenary pilots by the Mohamed Siad Barre regime to conduct a brutal aerial campaign against Hargeisa and other northern cities in 1988–1989. The second is a contemporary genocide against Somaliland that the current Federal Government of Somalia is seeking military support from Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia for similar purposes. This analysis aims to present the available facts, highlight potential parallels, and assess the implications of such external involvements.

The Historical Case:

Foreign Mercenaries in the 1988–1989 Bombing Campaign:

In May 1988, the Somali National Movement (SNM) launched a major offensive in northern Somalia (present-day Somaliland), capturing parts of Hargeisa as they could no longer watch Barre’s regime systematically wiping Isaq people out from the Horn of Africa . The Siad Barre regime responded with a massive and indiscriminate military campaign aimed at crushing the rebellion and terrorizing the civilian population, actions widely characterized as war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Isaaq genocide, also known as the Hargeisa Holocaust.

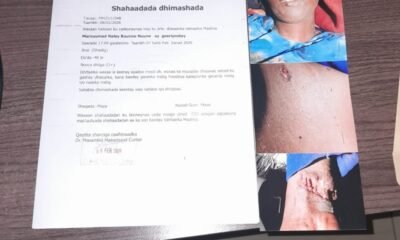

Recruitment and Origin of Pilots:

To supplement its air force, the Barre regime hired foreign mercenaries . These pilots were primarily recruited from South Africa and former Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

One specific account notes that “bombing raids on the towns for one month were conducted mainly by mercenaries recruited in Zimbabwe.

These mercenaries operated during the peak of the conflict in 1988–1989. They flew missions from the Hargeisa airport, targeting not only SNM positions but also conducting widespread, indiscriminate bombing of civilian areas in Hargeisa and surrounding regions. Their role was to provide the regime with additional aerial strike capacity for a campaign of collective punishment.

The objective was to support the Somali army in suppressing the civilians uprising by terrorising the civilian population through sustained aerial bombardment. This campaign resulted in the destruction of a large part of Hargeisa, Burao and caused thousands of civilian casualties, and is a central element of the planned and executed genocide against the Isaaq clan. The use of mercenaries allowed the regime to conduct this intense bombing campaign despite potential constraints within its own military.

Recent reports and statements indicate that the current Federal Government of Somalia is seeking direct military assistance from foreign states specifically Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia for operations against Somaliland with the aim of committing genocide again past genocide survivors. A prominent fact is that Somalia’s Minister of Defence requested his Saudi counterpart to conduct airstrikes against Somaliland and to facilitate the capture of its president.

Turkey already has a significant military training and infrastructure presence in Somalia. The current evidence suggests this partnership could be expanded to include direct combat support.

Egypt and Saudi Arabia are being asked by Somalia to provide aerial military capabilities, reminiscent of the mercenary model used in 1988, though ostensibly through state-to-state agreements rather than private contracts.

Turkey has already deployed F-16 fighter jets to Somalia to be precisely part of this plan.

As of February 2026, these specific evidence of requests for bombing and capture operations reflect heightened tensions between Mogadishu and Hargeisa and a genuine fear in Somaliland of a return to large-scale, externally supported violence.

Historical Parallels:

The current requests evoke a direct parallel to the 1988 strategy, the Somali government seeking external aerial firepower to resolve its 60 year occupation with Somaliland. The historical precedent shows that such outsourcing of violence can lead to disproportionate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, with lasting humanitarian and political consequences.

Key Differences:

The historical case involved private mercenaries, while current evidence point to formal state actors.

The 1988 campaign occurred during the Cold War with less international scrutiny. Today, any such overt foreign military action would face immediate global attention and potential legal ramifications under international law.

Potential Implications:

For Somaliland this reinforces its deep-seated security fears and unhealed genocide scars and it could destabilize the relative peace maintained since the 1990s.

For Regional Stability, it could draw neighboring states into a proxy conflict, escalating tensions in the Horn of Africa.

For International Law, it would raise serious questions about the legality of cross-border military actions at the request of a government against a territory that has maintained de facto independence for decades and has legitimate and legal state continuity.

Conclusion:

The use of South African and Rhodesian mercenary pilots by the Siad Barre regime in 1988–1999 is a documented historical fact that exemplifies how external military capabilities can be harnessed for internal repression, resulting in atrocities. If Israel would not recognise Somaliland , Somalia was seeking support from Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia for assisting with their planned genocide.

The international community must remain vigilant to ensure that external military involvement, in any form, does not enable further human mainly by mercenaries recruited in Turkey, Egypt or Saudi Arabia.

This recurring threat of genocide from Somalia to Somaliland which is a de jure state underscore the critical need for the failed state of somalia respecting for international law and living peacefully with its neighbours to prevent any recurrence of the devastating genocide and violence witnessed by somaliland in the past.

Somaliland is not claiming a right to secede from a functioning state. it is reclaiming a pre-existing statehood after a failed merger. This makes its case sui generis.

By Mo Saeed

Somaliland legal research (SLR)

Opinion

Turkey’s Selective Morality: From the Ruins of Gaza to the Red Sea

By Saleban Dahir Abdillahi (Dogox)

As the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza continues to redefine the moral landscape of the 21st century, Turkey has positioned itself as the preeminent defender of Palestinian rights. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has skillfully utilized the global stage to denounce Israeli military actions, invoke the sanctity of international law, and challenge the “double standards” of the West. Yet, beneath this veneer of pan-Islamic solidarity lies a discordant pattern of selective morality, dictated not by justice, but by cold strategic self-interest.

This inconsistency was laid bare following the transformative events of December 26, 2025, when Israel became the first UN member state to formally recognize the Republic of Somaliland. Ankara’s response—a swift condemnation labeling the move as “interference in Somalia’s internal affairs”—reveals a profound contradiction. While Turkey preserves its right to maintain a complex, multi-layered relationship with Tel Aviv, it simultaneously denies the same diplomatic agency to Somaliland, a nation that has maintained democratic stability for over three decades.

The Pragmatism of Trade vs. The Rhetoric of Resistance

Turkey’s rhetorical support for Gaza is unmatched in its theatrical intensity, yet the material reality suggests a “managed recalibration” rather than a clean moral break. Despite the official trade suspension announced in May 2024, data from 2025 indicates that Turkish exports to Israel persisted via third-party channels, reaching nearly $394 million in the first half of the year alone.

For observers in Hargeisa, the takeaway is clear: Ankara views its own relationship with Israel through the lens of “strategic necessity” while framing Somaliland’s diplomatic outreach as an ideological betrayal. This widening gap between Ankara’s populist anti-Israel posturing and its continued economic pragmatism suggests that Palestinian solidarity has become a tool for domestic signaling rather than a consistent foreign policy priority.

The Spaceport and the Patronage of Mogadishu

Turkey’s role in Somalia is often presented as a model of altruistic Muslim solidarity. In practice, however, the relationship increasingly resembles a traditional patronage system designed to project Turkish power into the Indian Ocean. In January 2026, Turkey officially broke ground on its Somali Spaceport—an equatorial launch facility in the Jamaame region designed to grant Ankara independent access to orbit.

This deepening military-industrial entanglement explains Ankara’s hostility toward Somaliland’s developmental gains. Turkey does not merely seek the “unity” of Somalia; it seeks a monopoly of influence over the western shores of the Red Sea. When Turkey condemns the “destabilizing” nature of Israeli recognition for Somaliland, it conveniently ignores that its own expansion—including the massive TURKSOM military base and now a strategic spaceport—is equally transformative for the regional security architecture.

The Kurdish Mirror and Moral Credibility

Turkey’s claim to moral leadership is further eroded by its domestic record. The systematic repression of Kurdish political movements and ongoing military operations in northern Syria and Iraq contrast sharply with Ankara’s defense of self-determination in Gaza. A government that denies fundamental rights to millions of its own citizens struggles to present itself as a global champion of justice. This “Kurdish mirror” suggests that Turkey supports statehood and human rights only when they serve its specific geopolitical ambitions.

Asserting Somaliland’s Sovereign Narrative

In the wake of the December 26 recognition and the subsequent January 6, 2026, visit of Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar to Hargeisa, Somaliland must shift its diplomatic posture from seeking “permission” to asserting its restorative sovereignty. To counter Ankara’s selective morality, Somaliland should adopt a three-pillar strategy:

The 1960 Successor State: Hargeisa must emphasize that its recognition is not a “secessionist” act, but the restoration of its 1960 status as a sovereign state. By anchoring legitimacy in its original colonial borders, Somaliland aligns with the African Union’s own Charter regarding the sanctity of borders inherited at independence.

Sovereign Reciprocity: Somaliland should formally review the operations of Turkish-affiliated offices and cultural councils, such as the Maarif Foundation. If Ankara continues to leverage its Mogadishu-based projects to undermine Somaliland’s interests, Hargeisa is justified in re-evaluating the presence of Turkish entities within its borders.

Diplomatic Equality: Somaliland must demand that all international actors—including Turkey—interact through formal sovereign protocols. The era of “shadow diplomacy” is over; Hargeisa has demonstrated it is the only reliable, democratic partner in a volatile region.

Conclusion

Turkey’s reaction to Somaliland’s recognition reveals a broader pattern of control and contradiction. While Ankara speaks the language of justice, its actions—from its indirect trade with Israel to its spaceport in Jamaame—tell a story of calculated strategic gain. For Somaliland, the challenge is to assert its agency with the confidence of a state that has earned its place in the world. For Turkey, the question is more fundamental: can moral leadership truly be claimed when it is applied so selectively?

Opinion

Shared Scars: The Parallel Existential Struggles of Israel and Somaliland.

The histories of Israel and Somaliland are etched with the profound trauma of genocide and defined by a continuous struggle for survival against hostile neighbors. Though separated by geography and culture, their historical converge on a stark common ground: both are nations forged in the fires of catastrophic violence, fighting for their very existence against adversaries dedicated to their erasure.

The Shadow of Genocide:

For both peoples, the term “genocide” is not an abstract historical concept but a lived, painful reality that shapes their national identity and geopolitical posture.

Israel and the Holocaust:

The foundation of modern Israel is inextricably linked to the Holocaust, the systematic murder of six million Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators. This unparalleled catastrophe demonstrated the existential vulnerability of the Jewish people without a sovereign state, a core motivation for Israel’s establishment and reclaiming the homeland of their ancestors with the determination to ensure “never again.”

Somaliland and the Isaaq Genocide:

Between 1987 and 1989, the regime of Somali dictator Mohamed Siad Barre perpetrated a systematic campaign of annihilation against the Isaaq clan, the majority population of Somaliland. This campaign, officially recognized as a genocide by a United Nations investigation, included the near-total destruction of major cities. Hargeisa, Somaliland’s capital, was approximately 90% destroyed, leading to its grim nickname, “the Dresden of Africa”. The violence was executed with brutal efficiency, involving indiscriminate aerial bombardments. Notably, the Somali regime employed foreign mercenaries, including South African mercenary pilots who conducted airstrikes against civilian areas.

The regime’s propaganda of dehumanising the Isaaq people, labeling them as Jewish with derogatory epithets to justify their extermination.

The Perpetual Threat of Hostile Neighbours:

The trauma of genocide is compounded by an ongoing, fundamental conflict with neighboring entities that reject their right to exist.

Israel’s Regional Adversaries:

Israel’s primary conflict is with Hamas, which is formally dedicated to Israel’s destruction. Hamas launched a large-scale attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 firing thousands of rockets and sending fighters into Israeli towns, killing civilians and soldiers and taking hostages. This conflict is embedded within a broader regional confrontation with state and non-state actors, many backed by Iran, which also openly seeks to eliminate the Jewish state. This includes persistent threats from Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen.

Somaliland’s Struggle with Somalia:

Since restoring independence in 1991, Somaliland’s most pressing existential threat is the Federal Republic of Somalia and their Alshabab cohort. These entities are unreasonably against somaliland’s restoration of sovereignty in 1991. Mogadishu wages a relentless diplomatic and, at times, military campaign to undermine Somaliland’s sovereignty. This includes supporting proxy forces within Somaliland’s borders. The Las Anod conflict in 2023 is a prime example, where Somali-backed SSC-Khatumo forces fought against the Somaliland National Army. Mogadishu is constantly fuelling internal strife in Somaliland by providing military hardware to minority clans, viewing it as a strategy to destabilize the breakaway region.

Facing New Existential Fears:

The struggle for recognition and security is a daily reality, with recent developments exacerbating these fears.

For Somaliland, the prospect of a renewed large-scale conflict is a palpable fear. These anxieties were heightened in early 2026 when Somalia’s Defence Minister, Ahmed Moalim Fiqi, appealed to Arab nations, Turkey and Egypt , “especially Saudi Arabia,” to take action against Somaliland’s leadership. While Fiqi’s public comments focused on opposing Somaliland’s independence and its relations with Israel, his rhetoric—calling for international pressure and drawing parallels to other regional conflicts—is interpreted in Hargeisa as a direct threat to its survival, stirring memories of past genocide.

Conclusion: An Unending Fight for Existence

Israel and Somaliland, though vastly different in scale and international standing, are bound by a shared historical arc of suffering and resilience. The Holocaust and the Isaaq genocide are foundational tragedies that inform their unwavering focus on self-preservation. Today, both navigate a complex and hostile regional environment where neighboring powers fundamentally challenge their legitimacy. For Israel, the threats are well-documented and widely recognized. For Somaliland, the fight is for the world to acknowledge its historical trauma and its ongoing battle for survival against a neighbor that once sought to eliminate it and continues to deny its right to exist. Their stories are a sobering reminder of how the scars of genocide shape a nation’s destiny and its perpetual struggle for a secure future.

Mo Saeed

Somaliland legal research (SLR)

Opinion

Diplomatic Recognition and the Weight of Legal History: Re-examining the Case for Somaliland

A critical examination exposes not only the weakness of the arguments against Somaliland but also how major powers like Turkey are leveraging a weakened Somalia to enforce a strategic deadlock that contradicts legal history and regional stability.

The Legal Vacuum at the Heart of the Union

The debate is not merely political but rests on a foundational legal question: was the 1960 union lawful.

Evidence shows it was not, making Somaliland’s re-emergence a restoration of sovereignty, not an act of secession.

Following independence on June 26, 1960, the State of Somaliland passed “The Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law” to formalize the merger with the soon-to-be-independent Somalia. The plan was for an identical international treaty to be signed by both sovereign states.

However, the southern legislature in Mogadishu did not ratify this document. On June 30, 1960, it approved an Act of Union “in principle” but requested the governments “establish a definitive single text” for later approval. This definitive, mutually-signed treaty was never created. Legal scholar Paolo Contini concluded that “the Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law did not have any legal validity in the South,” and the “in principle” approval was “not sufficient to make it legally binding”. Subsequent attempts to formalize the union retroactively in 1961 could not erase this initial legal defect.

The distinction between “restoration” and “secession” is fundamental to understanding the dispute:

|

Basis of Claim |

Restoration of Sovereignty (Somaliland’s Argument) |

Secession / Breakaway (Opponents’ Framing) |

|

Legal Foundation |

Reassertion of a pre-existing, independently achieved sovereign status. |

Attempt to carve a new state from an existing, sovereign nation. |

|

Key Event (1960) |

A voluntary union based on a defective, non-ratified treaty that failed to legally extinguish sovereignty. |

A completed political merger creating a new, singular sovereign entity (the Somali Republic). |

|

International Law |

Argues state continuity was merely interrupted, not terminated. |

Violates the principle of territorial integrity (uti possidetis juris) of the post-1960 Somalia. |

This unresolved legal ambiguity is central to Somaliland’s case for international recognition. Its 1991 declaration was not a bid for novelty but a return to a sovereign status that, it argues, was never lawfully surrendered.

Turkey’s Strategic Calculus: Acting as Guarantor While Exploiting Vulnerability

Turkey’s vehement opposition to Somaliland’s recognition must be scrutinized beyond diplomatic solidarity.

Since 2011, Turkey has embedded itself as Somalia’s foremost external patron, providing over $1 billion in humanitarian aid, building its largest global embassy in Mogadishu, and operating a major military base that has trained thousands of Somali troops. This positions Turkey as Somalia’s de facto security guarantor, a role solidified by a 2024 defense pact where Turkey agreed to rebuild and train the Somali Navy in exchange for 30% of maritime resource revenue. Turkey has also mediated critical disputes for Mogadishu, such as the 2024 agreement with Ethiopia.

However, this guarantor role operates alongside deep economic investments that critics argue amount to exploitation of a fragile state. Turkish companies hold critical infrastructure contracts, including the management of Mogadishu’s airport and seaport. A plan is underway for Turkish Airlines to take a strategic stake in Somali Airlines and build a $1 billion “New Mogadishu International Airport”. Furthermore, a confidential energy deal grants Turkey rights to explore and potentially extract Somalia’s offshore oil and gas reserves. This creates a pattern where strategic influence is converted into long-term economic control over Somalia’s key assets.

This deep involvement unfolds against a dire humanitarian backdrop in Somalia, marked by conflict, climate shocks, and severe funding cuts. Projections indicate nearly half of all Somali children under five could face acute malnutrition by mid-2026. The stark contrast between high-level security and infrastructure deals and the suffering of Somalia’s population fuels allegations that external powers are prioritizing strategic and resource competition over the welfare of the Somali people. Critics view Turkey’s policy as exploiting Somalia’s weakness—its need for a security guarantor against internal and external threats—to secure preferential access to resources and geopolitical influence, all while publicly championing Mogadishu’s sovereignty to block Somaliland’s recognition.

Conclusion: Toward a Principles-Based Diplomacy.

The diplomatic storm over Somaliland’s recognition is a clash between historical legal fact, contemporary humanitarian need, and raw political expediency. Dismissing Somaliland’s claim requires ignoring the documented legal failures of its 1960 union with Somalia. Meanwhile, the opposition from powers like Turkey, while framed as protection of sovereignty, often serves to consolidate their own influence within a dependent Mogadishu, even as the basic needs of Somalia’s population go unmet.

A truly principled approach would require the international community to engage seriously with Somaliland’s substantive historical and legal case, separate from the geopolitical gamesmanship of external powers. It would also demand that those acting as guarantors for Somalia be held accountable for aligning their security and economic engagements with the urgent humanitarian needs of the Somali people. The alternative—upholding a fictional unity while states jockey for resources amidst widespread suffering—serves only the interests of those who profit from sustained ambiguity and continued crisis in the Horn of Africa.

Mo Saeed

Somaliland legal research (SLR)

Opinion

When Envy Becomes a Disease: Somalia’s Sick Obsession with Somaliland

If you ever wondered why Somalia remains arguably the worst-governed country on Earth after 30 years of turmoil, look no further than the leaders who have run the show for the past two decades. It’s no secret—Somalia’s political class is suffering from a mental disorder that might best be called the “Somaliland Syndrome.”

This affliction manifests as an obsessive, pathological envy of Somaliland’s success, coupled with an absolute inability to replicate any of it.

While Somaliland quietly builds peace, stable governance, and economic progress, Somalia’s leaders appear trapped in a delusional loop, fixated on erasing Somaliland rather than improving their own failed system. Their diagnosis? “Somaliland is the disease. If only we could destroy it, everything would be fine.” Reality? Somaliland’s stability is the cure Somalia desperately needs.

This sickness explains a lot: rampant corruption, terrorist infiltration, foreign puppeteering, and endless power struggles are just symptoms.

The Somali state’s leadership—most glaringly the Himilo Qaran political party led by former President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed—is the textbook case.

Here you have a man once tied to the Islamic Courts Union and arguably the spiritual father of Al-Shabaab, now championing national unity and elections. The irony could not be thicker.

How can a leader with “Somaliland Syndrome”—who spends more time fixating on Somaliland republic that has nothing to do with him—preside over a system so thoroughly entwined with terrorist groups and corruption? It’s like a sick man lecturing the healthy on how to run a marathon.

The recent clashes in Gedo—where the federal government’s forces face off with Jubbaland militias—highlight this dysfunction.

Himilo Qaran shamelessly blames Mogadishu for “escalating” violence, yet fails to acknowledge that the very government it opposes is the only entity attempting to assert order over a fractured state. Instead, it warns of “enemies approaching Mogadishu,” as if Somalia’s greatest enemy isn’t internal chaos and kleptocracy.

And who is behind these “enemies”? The party’s leadership has long been entangled with forces that either flirt with or actively support militant Islamism. It’s no surprise they decry federal military deployments as “political,” while using rhetoric that fans division.

Somalia’s government, meanwhile, accuses Jubbaland leader Ahmed Madobe of launching “criminal attacks” to resist federal authority. This tit-for-tat violence reflects a failed system where regional warlords operate as de facto rulers, and central governance is a fragile illusion.

So while Somaliland invests in governance, infrastructure, and diplomacy, Somalia remains mired in “Somaliland Syndrome,” a deadly cocktail of denial, envy, and self-destruction. The rest of the world watches, bemused and horrified, as Somalia’s political class preaches about elections while their country falls apart.

The bitter truth is that Somalia’s political sickness will only be cured by acknowledging Somaliland’s success—not by vilifying it. Until then, expect more chaos, more terrorism, and more tragic irony from a leadership too sick to heal their own nation.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect WARYATV’s editorial stance.

Opinion

Djibouti: The Small Nation Carrying Global Weight

Djibouti: A Global Public Good for Regional Stability and Development.

Economists call a public good something that benefits everyone, without exclusion or rivalry. Diplomats know that some nations—by virtue of geography, history, and posture—embody this principle far beyond their borders or population size. Djibouti is one of them.

Our republic is not only a sovereign state serving its own citizens. From the moment of independence, Djibouti has stood as a regional and global public good: a place of anchorage, solidarity, and stability in one of the world’s most turbulent neighborhoods.

A legacy of solidarity

From the beginning, Djibouti has carried the burdens of its region. We twice received waves of Ethiopian refugees during their darkest crises. We opened our borders to Somalis fleeing civil war. We sheltered Yemenis crossing the Red Sea to escape violence, and we welcomed Eritrean families driven out by conflict. Each time, Djibouti paid the human and financial cost of solidarity—never as a matter of choice, but of duty.

This tradition continues. In 2023–24, when Sudan’s crisis escalated, Djibouti became the main hub for humanitarian evacuation, hosting, protecting, and relocating thousands of civilians, diplomats, and aid workers.

A humanitarian lifeline

Djibouti is not only a platform for trade. It is the beating heart of humanitarian logistics on the East African coast. If food and aid continue to reach millions of Yemenis today despite a devastated warzone, it is because Djibouti’s ports serve as the UN’s inspection and distribution base. Quietly, but indispensably, Djibouti has become a lifeline in the global humanitarian chain.

Today, that lifeline is under unprecedented strain. Following a recent and deeply regrettable decision by one of the largest contributors to UN agencies, the UNHCR has scaled back its role in providing basic life services to refugees. The consequences fall directly on Djibouti. With our limited national resources, we are now left to feed and sustain more than 50,000 refugees within our borders. These numbers do not even account for the additional 100,000-plus migrants who cross our territory illegally each year on their way to the Gulf states and Europe. These migrants figures are much more in reality and the main reason of migration is related to climate change consequences as well as lack of opportunities in their respective countries For a nation of barely one million people, this burden is staggering—and it is being carried in silence.

An investor in its neighbors’ future

Djibouti has never been content to be a passive aid recipient. Together with Ethiopia, we co-invested nearly 10 Billions over two decades—in infrastructure that connects not only us but our neighbors. Since the late 1990s, our port capacity has grown fourteen-fold. These facilities are not simply Djiboutian assets; they are regional arteries.

Without them, Ethiopia’s transformation would have been impossible. Over 100 million Ethiopians depend on Djibouti for food imports, energy supplies, and access to world markets.

Some outsiders mistakenly or purposely claim that Djibouti’s Ports & logistics services costs amount two billion dollars per year to Ethiopia. The truth is far more modest: the direct financial flow does not exceed 500 million dollars per year. But numbers miss the point. What matters is the strategic impact: without Djibouti, Ethiopia’s economy would be throttled, and the Horn of Africa’s development trajectory would look radically different.

Why I write today

These facts are not unknown to our partners. So why underline them now?

First, because 15 years of experience in development policy have shown me what Djibouti has contributed—and still contributes—to its region and the wider world. Second, because I am frustrated by the mechanistic formulas too often applied to us. To reduce Djibouti to a million citizens or a modest GDP is to erase its true role: a global public good whose stability and solidarity benefit hundreds of millions.

Towards a fair partnership

Supporting Djibouti is not charity. It is a collective investment in global security.

Investing in Djibouti’s infrastructure secures the flow of maritime trade that powers the global economy.

Strengthening Djibouti’s social resilience contains destabilizing spillovers from fragile neighbors.

Supporting Djibouti’s diplomatic and humanitarian role provides the Horn of Africa with a credible platform for mediation and relief.

As the traditional Allocations formula from IDA, ADF, IDB etc. is good for large or sized states.

This requires new formulas, innovative financing tools, and—above all—a fair partnership. Not despite Djibouti’s size, but because of its unique function.

An undeniable truth

Djibouti is small on the map but immense in purpose. It is a strategic crossroads, a humanitarian lifeline, a security anchor, and a vital node of world commerce.

My intention is not to provoke polemics, but to restate a truth that can no longer be ignored: without Djibouti, the Horn of Africa would not have experienced the progress it has achieved.

It is time to move beyond arithmetic models and face reality. Djibouti is a global public good. Supporting it is not supporting a small country—it is securing regional resilience, the Horn’s cohesion, the stability of world trade, and ultimately, global peace.

Ilyas M. Dawaleh

Minister Of Economy & Finance,in Charge of Industry, Republic of Djibouti.

Brotherhood at the Palace: Irro and Guelleh Forge New Horn Alliance

In the Horn of Africa, Unity Offers Power, Division Risks Peril

From Vision to Victory: Djibouti’s Political Mastery as Youssouf Assumes AU Chair

Djibouti and Somaliland Reignite Historic Brotherhood with President Irro’s Landmark Visit

Djibouti’s Mahamoud Secures Historic AU Commission Chairmanship

Why Djibouti’s Mahamoud Ali Youssouf Will Win the AU Chairmanship

Opinion

In the Horn of Africa, Unity Offers Power, Division Risks Peril

More than 3.4 billion people worldwide now live in countries that spend more on interest payments than on health. For the Horn of Africa, the arithmetic of survival tilts heavily toward integration over isolation. The deficit of trust across the region often suffocates collective action. Young people, unconvinced that tomorrow will be better, vote with their feet, crossing borders or seas in search of opportunities that home economies cannot yet provide.

The Horn of Africa has reached a hinge moment in a turbulent century. Pandemics, climate shocks, financial tremors, and geopolitical rivalries are rearranging global power, forcing countries to decide whether to hunker down behind borders or ride out the storm together.

For the Horn, the question is haunting. The refrain, whether to retreat behind borders while each country fends for itself, echoes from highlands to coasts. Isolation can soothe short-term fears; however, partnership is now the objective measure of strength. Regional integration is no longer a lofty dream. It is the complex calculus of survival.

Alarmingly, the costs of fragmentation are already visible. Border frictions delay trucks and convoys, adding days to delivery times and scaring off investors. Regulatory mismatches snarl digital start-ups and block power grids from linking. A deficit of trust suffocates collective action, while young people, unconvinced that tomorrow will be better than today, leave to seek opportunities abroad.

Nonetheless, most damaging is the disunity that turns the Horn of Africa into a strategic chessboard on which outside powers manoeuvre, each move widening the region’s fault lines. No state, however large or resource-rich, can flourish for long in such an environment.

Djibouti has chosen a different path. Its leaders insist on openness, dialogue, and connection. More than a logistics platform, Djibouti aspires to be a catalyst for cooperation, hosting peace talks, laying fibre-optic cables, and keeping its ports open to all.

If the geography of the Red Sea lanes, shared watersheds, and cross-border pastoral routes ties the Horn of Africa together, then political will can turn geography from a curse into a blessing.

The Horn of Africa is not condemned to crisis. It possesses the raw materials to become a laboratory of African solutions to Africa’s problems and a driver of shared prosperity. Ports can serve entire corridors, not just one flag. Peace can rest on dialogue, not fear. National pride can bind people together instead of driving them apart.

The region is not a powder keg. It can be a collective powerhouse if we choose unity.

Imagine a region powered by pooled energy grids, stitched together by seamless roads and rail, and wired through interoperable digital platforms. Envision supply chains that shrug off climate shocks because farmers, traders, and relief agencies coordinate forecasts, seeds, and storage. Imagine a workforce of young women and men who swap ideas instead of arms.

Indeed, such a future is attainable, but only if firm foundations are laid. There should be leadership that breaks cycles of grievance and institutions trusted to mediate disputes. Regular forums, such as councils, joint commissions, and early-warning systems, that replace rumour with facts should be encouraged. While joint investment in public goods, such as infrastructure, innovation, and climate resilience, needs to be reinforced, the most elusive aspect, a culture of trust, should be built patiently, transaction by transaction, election by election, and deal by deal.

Sovereignty and solidarity need not collide. When interdependence is managed, bridges guard national interests better than walls can.

Djibouti’s claim to neutrality should be viewed as a responsibility, not an indifference. Three pillars support it.

It originates from an exceptional geography, serving as a gateway that links Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. Its diplomatic credibility is earned by outreach to every camp without surrendering judgment. It has an enduring stability, upheld by institutions that facilitate political dialogue and provide predictable governance.

The African Union (AU), IGAD, the Arab League, the United Nations (UN), and global partners acknowledge these endowments. Djibouti, however, recognises that credibility erodes if it rests on inertia. Djibouti wants, and can go further, not on the ways of competition, but contribution and cooperation.

Its leaders outline three initiatives to match these pillars with action. The Arta Centre for Regional Mediation & Peace would train mediators, advance strategic research, and weave elders, youth, and women into peacemaking. An Annual Forum on Security, Peace, & Cooperation in the Horn of Africa, a Davos for Peace, so to say, would gather leaders, businesses, civil society, scholars, and mediators to compare notes before crises mature.

Lastly, a set of neutral trilateral diplomacy mechanisms would provide off-ramps from binary confrontations, thereby lowering the temperature of regional disputes before they escalate.

This agenda is based on the principles of neutrality as a duty, stability as a regional public good, and African solutions to African challenges. As global multilateralism wanes, principled regional leadership becomes increasingly vital. Djibouti’s vocation is to connect, convene, and integrate, never to dominate.

There is no concealed agenda here, only a sincere desire to build a community of shared destiny.

Much of this outlook bears the imprint of President Ismail Omar Guelleh, hailed at home and abroad as a charismatic statesman whose lifelong dedication blends wisdom, foresight, and an unwavering commitment to regional peace. For more than two decades, he has steered Djibouti through the Horn of Africa’s minefields, betting consistently on dialogue over discord and integration over isolation.

Neighbours in search of mediators often arrive in Djibouti City first, confident they will find a steady hand and a discreet ear.

The moment, though, belongs not to any single leader but to the region’s citizens. They should offer a clear wager. Those who invest in peace, dialogue, and shared prosperity are most welcome. Profiteers from mistrust should not be.

Unity should no longer be a slogan but the only viable security policy. The Horn of Africa’s future will be decided by those willing to trade suspicion for cooperation. The choice, therefore, is urgent, and still ours to make.

Ilyas M. Dawaleh

Minister Of Economy & Finance,in Charge of Industry, Republic of Djibouti. Secretary General of RPP

@Ilyasdawaleh

-

Terrorism1 month ago

Terrorism1 month agoAmerica Pulls Back From Somalia but Doubles Down Next Door

-

Somaliland2 months ago

Somaliland2 months agoF-35s Over Hargeisa: The Night Somaliland’s Sovereignty Went Supersonic

-

Somalia2 months ago

Somalia2 months agoAid Destroyed, Trust Shattered: Somalia Loses U.S. Support for Good

-

Opinion2 months ago

Opinion2 months agoTurkey’s Selective Morality: From the Ruins of Gaza to the Red Sea

-

Terrorism2 months ago

Terrorism2 months agoForeign ISIS Pipeline Exposed: Puntland Captures Dozens of Non-Somali Fighters

-

Somaliland2 months ago

Somaliland2 months agoSomaliland at Davos: The Moment Somaliland Entered the World’s Inner Circle

-

Diplomacy2 months ago

Diplomacy2 months agoEthiopia–Israel Axis Strengthens as Regional Stakes Rise

-

Top stories2 months ago

Top stories2 months agoEuropean Troops Land in Greenland as US Pushes Takeover