Top stories

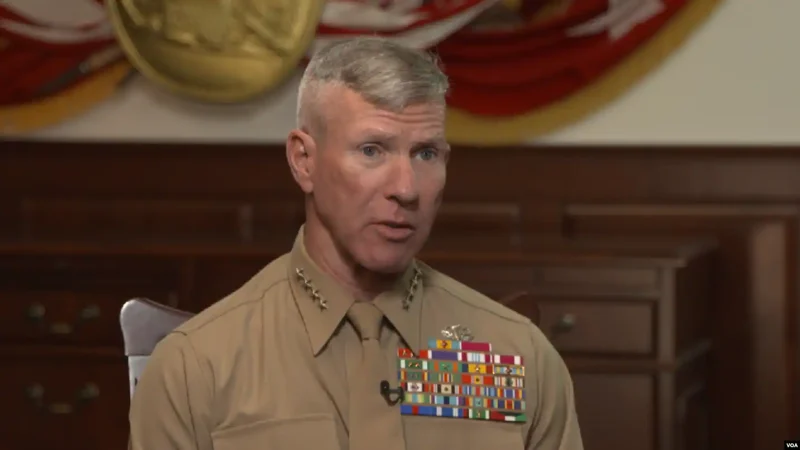

Naval Shortfall Sparks Crisis: U.S. Marines Face Amphibious Ship Drought

Pentagon Scrambles as Key Naval Assets for Rapid Response Fall Critically Short, Risking Global Marine Operations.

The U.S. Marine Corps is confronting a dire shortage in amphibious warfare ships, spotlighting a critical vulnerability in America’s military posture. Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Eric Smith’s stark admission outlines a scenario where marine deployability is hamstrung not by lack of personnel or intent, but by a sheer shortage of necessary naval platforms—the amphibious ships.

These ships, essential for transporting Marines during assaults, now represent a glaring gap in the U.S. military’s operational capabilities. According to Gen. Smith, the current fleet is insufficient to meet the global demands for Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs), specialized groups that respond rapidly to international crises. This shortfall arrives at a time when geopolitical tensions necessitate robust American military presence worldwide, particularly in regions like the Indo-Pacific, where the specter of conflict with nations like China looms large.

The situation is aggravated by prolonged maintenance issues and a dwindling fleet, exacerbated by years of budget constraints and shifting military priorities. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report reveals that about half of the amphibious fleet is in poor condition, a distressing signal of the underlying systemic issues within naval logistics and maintenance regimes.

The implications of this shortage extend beyond mere operational inconvenience. They signify a potential crisis in military readiness, with Gen. Smith suggesting that the Marine Corps’ ability to project power and respond to international incidents is being critically undermined. This comes at a time when the strategic necessity for rapid deployment capabilities has never been more acute, as global hotspots proliferate and the U.S. faces increasing pressure to maintain its role as a global stabilizer.

The Pentagon’s response, though urgent, faces bureaucratic and logistical hurdles that could delay effective resolution. As the Marine Corps and Navy grapple with these challenges, the broader implications for U.S. security interests are clear: without a capable and ready amphibious fleet, America’s ability to respond to international crises and maintain its strategic edge is at risk.

In conclusion, the shortfall in amphibious ships is more than a mere gap in the U.S. naval arsenal—it is a stark reminder of the broader challenges facing American military readiness in an increasingly unstable world. As the U.S. navigates these troubled waters, the resolve and resourcefulness of its naval forces will be crucial in ensuring that capability aligns with the country’s strategic ambitions.

Top stories

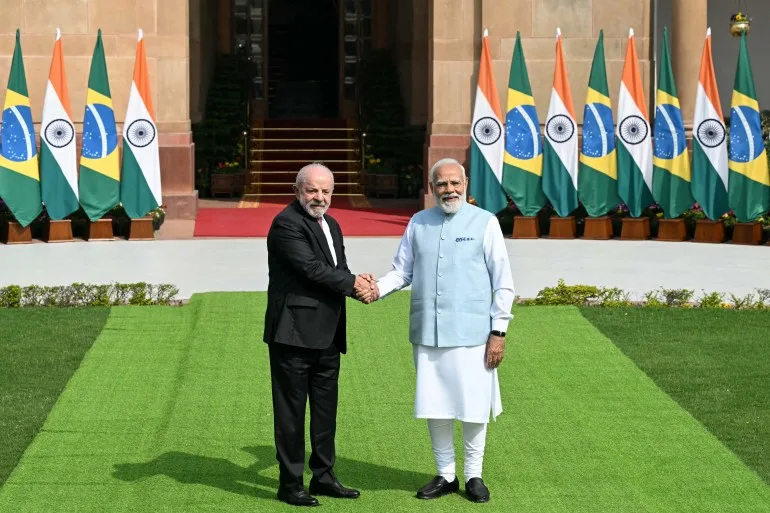

India Turns to Brazil in Strategic Minerals Push Against China

As China tightens its grip on rare earths, India is looking elsewhere. A new deal with Brazil could reshape global supply chains.

India and Brazil have signed a new agreement to deepen cooperation in critical minerals and rare earths, a move New Delhi hopes will reduce its dependence on China and strengthen supply chain resilience.

Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva met Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi on Saturday, where the two leaders discussed expanding trade and investment ties. Modi described the minerals agreement as a “major step towards building resilient supply chains.”

China currently dominates global mining and processing of rare earths and other critical minerals, materials essential for electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, smartphones, jet engines and advanced weapons systems. Beijing has tightened export controls in recent months, adding urgency to efforts by countries like India to diversify sources.

Brazil, which holds some of the world’s largest reserves of critical minerals after China, is well positioned to become a key alternative supplier. Lula said increasing cooperation in renewable energy and critical minerals was central to the “pioneering agreement” signed between the two countries.

Although specific details of the minerals pact have not been released, analysts say it reflects India’s broader strategy of securing long-term access to resources vital for industrial growth and clean energy transition. India has recently pursued similar supply chain partnerships with the United States, France and the European Union.

Beyond minerals, the two governments signed nine additional agreements spanning digital cooperation, health and other sectors. Modi called Brazil India’s largest trading partner in Latin America and set a target of pushing bilateral trade beyond $20 billion within five years.

According to trade data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity, Indian exports to Brazil reached $7.23 billion in 2024, led by refined petroleum products. Brazilian exports to India totaled $5.38 billion, with raw sugar among the top commodities.

For both nations, the agreement signals more than commercial ambition. As emerging powers, India and Brazil have increasingly framed their cooperation as strengthening the voice of the Global South in shaping new trade and energy rules.

In a world where control over minerals can shape geopolitical influence, their partnership may mark another step in the global race to loosen China’s grip on strategic resources.

Top stories

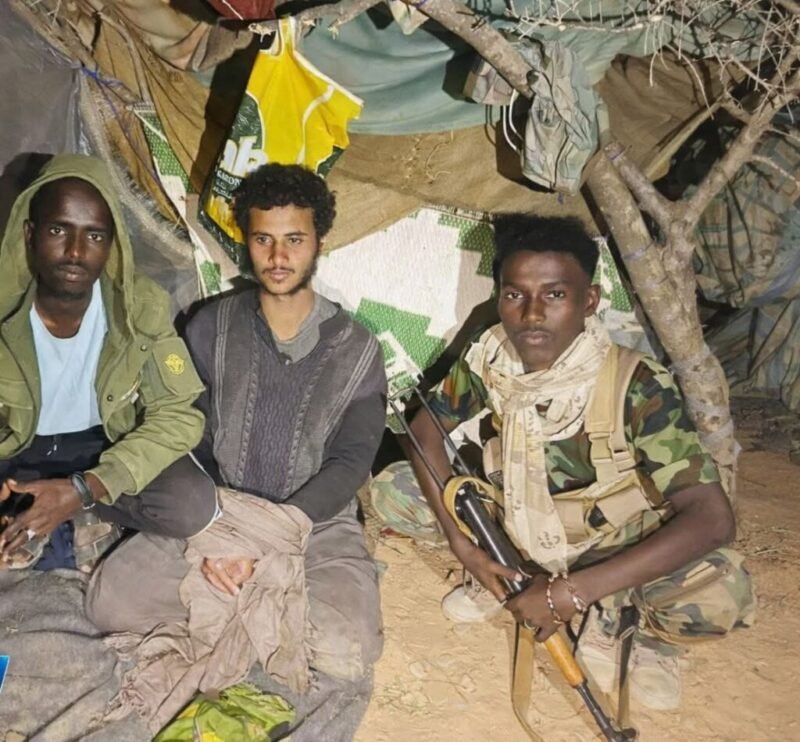

Yemeni ISIS Fighter Seized as U.S. Warplanes Strike

A foreign ISIS fighter captured at midnight — and a U.S. airstrike hours later. The battle for Al-Miskaad is intensifying.

Puntland security forces say they captured a suspected Islamic State fighter in a late-night operation in the Al-Miskaad Mountains, as the United States confirmed it carried out an airstrike in the same region days earlier.

According to officials overseeing operations in the mountainous area, the suspect was detained around midnight in the Tasjiic locality. He was identified as Bishaar Mohamed, described as a Yemeni national believed to be affiliated with ISIS.

Commanders said the man was unarmed at the time of his arrest and had reportedly fled from the Shankaala base in the Baalade valley — an area Puntland authorities describe as a key command hub for ISIS militants operating in the mountains east of Bosaso.

The capture comes amid intensified pressure on the group. In recent weeks, Puntland officials say several ISIS members, many of them foreign nationals, have surrendered to security forces as military operations expand deeper into the rugged terrain.

Separately, United States Africa Command confirmed that on February 16 it conducted an airstrike targeting ISIS fighters in Somalia. AFRICOM said the strike occurred in the Al-Miskaad Mountains, roughly 70 kilometers southeast of Bosaso, but did not disclose details on casualties or the specific targets.

The U.S. military has periodically supported Somali and regional forces with air operations aimed at degrading ISIS and al-Shabaab networks. While ISIS in Somalia is smaller than al-Shabaab, intelligence officials consider its mountainous strongholds strategically significant, particularly due to the presence of foreign fighters and suspected financial networks.

Puntland recently announced a shift in its military approach against ISIS — moving away from direct frontal assaults toward a strategy focused on encirclement and containment. Officials argue that isolating supply routes and tightening control around key bases will weaken the group’s operational capacity over time.

The twin developments — a ground arrest and an aerial strike — underscore a coordinated push to dismantle ISIS infrastructure in northeastern Somalia. Whether the new strategy yields lasting results may depend on sustained pressure, intelligence coordination, and the ability to prevent fighters from regrouping in the difficult terrain of Al-Miskaad.

Top stories

No Proof McConnell, McCarthy Discussed Slavery or Forced Pregnancy

A shocking “leaked call” spreads online — but is it real? There’s no credible evidence it ever happened.

Social media posts circulating in late February 2026 claim to show a transcript of a phone call between Senator Mitch McConnell and former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy discussing extreme proposals, including “bringing back slavery” and forcing eighth-grade girls to become pregnant.

There is no credible evidence that the conversation ever took place.

The videos, shared across Instagram, X, Facebook, Reddit and other platforms, feature an unidentified voice reading what is described as a leaked transcript. In the alleged exchange, the two Republican politicians are portrayed discussing slavery, state-funded religious schools, mass deportations and mandatory pregnancy for school graduation.

Fact-checkers found no reputable news organizations reporting on such a recording or transcript — an absence that raises serious doubts given the explosive nature of the claims. No details have been provided about who recorded the alleged call, when it supposedly occurred or how it was leaked. Some online posts reference July 2022 but offer no supporting evidence.

The content of the purported transcript also sharply contradicts both politicians’ documented public positions. While McConnell and McCarthy have opposed federal abortion protections and supported conservative judicial appointments, neither has publicly endorsed policies resembling the extreme and inflammatory statements described in the viral posts.

Both lawmakers have previously condemned slavery. In past public statements, McCarthy referred to the “evils” of slavery, while McConnell acknowledged it as a “stain on our history,” though he has opposed federal reparations.

The transcript also references Senator Lindsey Graham and “SCOTUS,” implying coordination around Supreme Court decisions. However, no independent evidence supports the authenticity of the alleged exchange.

Representatives for the lawmakers have not confirmed the transcript as genuine.

Experts warn that fabricated transcripts and AI-generated audio have become increasingly common tools for political misinformation, especially in election cycles. Without verifiable sourcing, audio proof or confirmation from credible outlets, the claim remains unsubstantiated.

In short, there is no proof that McConnell and McCarthy held the conversation described in the viral posts. The allegations appear to be based on an unverified and highly sensationalized script circulating online.

Top stories

Kremlin Declares Japan Relations ‘Reduced to Zero’

Eighty years after World War II, Russia and Japan still have no peace treaty — and now Moscow says there’s no dialogue at all.

Russia has declared that there is no ongoing dialogue with Japan toward a formal peace treaty, saying bilateral relations have effectively collapsed amid what the Kremlin describes as Tokyo’s “unfriendly” stance.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters Friday that ties between Moscow and Tokyo have been “reduced to zero,” making discussions about a long-delayed peace agreement impossible under current conditions.

“There is no dialogue, and it is impossible to discuss the issue of a peace treaty without dialogue,” Peskov said during a daily briefing. He added that Russia had not sought to end discussions but argued that the deterioration in relations had made progress unlikely.

The dispute centers on the Kuril Islands — known in Japan as the Northern Territories — a chain of islands seized by Soviet forces at the end of World War II. The territorial disagreement has prevented Russia and Japan from signing a formal peace treaty, leaving the wartime conflict technically unresolved nearly eight decades later.

In her inaugural address to parliament on Friday, Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi reaffirmed Tokyo’s long-standing position. Despite strained ties, she said Japan remains committed to resolving the territorial issue and concluding a peace treaty with Russia.

However, Moscow’s tone suggests little appetite for movement. Peskov indicated that without a change in the broader framework of relations — including Japan’s alignment with Western sanctions and policies following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — no agreements are likely.

The breakdown underscores the widening geopolitical divide between Russia and U.S.-aligned nations in Asia. Japan has imposed sanctions on Moscow and increased coordination with NATO partners, further complicating prospects for reconciliation.

For now, the decades-old territorial dispute remains frozen — another casualty of a broader global realignment that has hardened diplomatic positions on both sides.

Top stories

Taiwan? Trump’s Xi Comment Sends Shockwaves

When Washington says it’s “talking to Beijing” about Taiwan arms sales, Taipei listens carefully — and nervously.

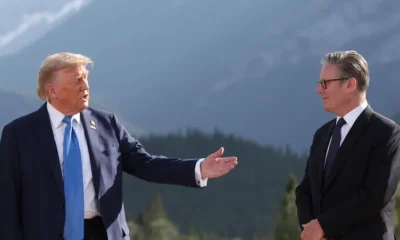

U.S. President Donald Trump has stirred unease in Taiwan after revealing he is discussing potential American arms sales to the island with Chinese President Xi Jinping, raising questions about whether longstanding U.S. policy guardrails are shifting.

Speaking to reporters Monday, Trump said: “I’m talking to him about it. We had a good conversation, and we’ll make a determination pretty soon,” referring to Xi’s objections to U.S. weapons packages for Taiwan. He added that he maintains “a very good relationship” with the Chinese leader.

The comments were unexpected and, according to several analysts, potentially sensitive. For decades, U.S. policy toward Taiwan has rested on carefully balanced principles designed to deter conflict without formally recognizing the island as independent.

One of those principles — known as the Six Assurances, issued under President Ronald Reagan in 1982 — explicitly states that the United States would not consult Beijing on arms sales to Taiwan. Analysts warn that even the perception of consultation could weaken that precedent.

Taiwan’s government has not publicly responded, as the island observes Lunar New Year holidays. But experts say the signal matters.

The United States does not have formal diplomatic ties with Taiwan, yet it remains the island’s primary security partner and arms supplier under the Taiwan Relations Act, passed in 1979. That law obligates Washington to provide Taipei with the means to defend itself and to regard threats against Taiwan as a matter of “grave concern.”

Beijing views Taiwan as part of its territory and has not ruled out the use of force to achieve unification. It routinely condemns U.S. arms sales and has intensified military pressure around the island in recent years.

In December, the Trump administration approved a record $11 billion arms package for Taiwan. Earlier this month, Xi reportedly told Trump during a phone call that Taiwan is “the most important issue” in U.S.-China relations and urged Washington to handle arms sales “with prudence.”

Analysts say Trump’s public acknowledgment of discussions could introduce uncertainty into the triangular relationship between Washington, Beijing and Taipei — particularly ahead of his planned visit to China in April.

For Taiwan, the concern is not necessarily that arms sales will stop, but that the issue might become negotiable in broader U.S.-China talks involving trade, technology or regional security.

As cross-strait tensions simmer, even rhetorical shifts can ripple far beyond diplomatic language. In Taipei, the question now is whether policy remains unchanged — or whether the foundations of U.S. strategic ambiguity are subtly moving.

Top stories

Washington Says It Shook Europe Awake

“Stop hitting the snooze button.” Washington claims Europe is finally listening.

The Trump administration has jolted Europe into action, according to the United States ambassador to the European Union, who said Washington’s tougher tone has helped push the continent to reassess its security and migration policies.

Andrew Puzder, the US ambassador to the EU, told Euronews that President Donald Trump and his team have effectively “woken up” Europe from complacency. Speaking on the broadcaster’s Europe Today program, Puzder described Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s recent address at the Munich Security Conference as both candid and constructive.

“It’s a hallmark of a great diplomat to say the things people need to hear, even if they don’t want to hear them,” Puzder said, characterizing Rubio’s speech as positive for the transatlantic alliance.

Rubio’s remarks came one year after Vice President JD Vance delivered a sharply critical speech at the same conference that unsettled European officials. This time, Puzder said, the audience was “very open,” and Rubio received a standing ovation.

Beyond security, migration featured prominently in the ambassador’s comments. Puzder argued that European policy has moved closer to the American position in recent years. He drew a distinction between what he called “managed migration” and “mass migration,” suggesting that large-scale arrivals over the past decade have created political and social strains across the continent.

When confronted with data showing that migrant arrivals to the European Union have declined from peak levels, Puzder said the broader concern is the cumulative impact of previous migration waves. He framed the issue as a long-term “civilisational challenge,” rather than a short-term numbers debate.

Climate policy also drew scrutiny. Puzder suggested that some European environmental measures may weigh on economic performance and GDP per capita, echoing criticism frequently voiced by the Trump administration.

Rubio’s European tour extended beyond Munich to Slovakia and Hungary, where he met Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, one of Trump’s closest allies within the EU. Asked about concerns over potential US interference ahead of Hungary’s April elections, Puzder dismissed the criticism, noting that Hungary is both a NATO ally and an EU member.

The broader message from Washington is clear: the transatlantic partnership remains intact, but the United States expects Europe to shoulder more responsibility — on security, migration and economic resilience — in what both sides increasingly describe as a new geopolitical era.

Top stories

India Seizes Iran-Linked Tankers, Expands Maritime Surveillance

Three tankers seized. Dozens of patrol ships deployed. India tightens its maritime net amid shifting global alliances.

India has seized three U.S.-sanctioned tanker vessels allegedly linked to Iran and significantly expanded maritime surveillance in its exclusive economic zone, according to a source with direct knowledge of the operation.

The vessels — Stellar Ruby, Asphalt Star and Al Jafzia — were intercepted roughly 100 nautical miles west of Mumbai after authorities detected suspicious ship-to-ship transfer activity. Such transfers are often used to obscure the origin of oil cargoes and bypass international sanctions.

Indian authorities have not issued a formal public statement confirming the identities of the vessels, but the source said the ships were escorted to Mumbai for further investigation. A February 6 social media post by the Indian Coast Guard referencing the interception was later deleted.

The United States previously sanctioned vessels with International Maritime Organization numbers matching those of the ships seized, including Global Peace, Chil 1 and Glory Star 1, under measures targeting Iran’s oil trade.

According to shipping data from LSEG, at least two of the vessels have direct links to Iran. Al Jafzia reportedly transported Iranian fuel oil to Djibouti in 2025, while Stellar Ruby has been flagged in Iran. Asphalt Star’s recent voyages centered around Chinese ports.

To strengthen enforcement, the Indian Coast Guard has deployed approximately 55 ships and up to 12 aircraft for continuous surveillance across its maritime zones.

The move comes amid improving relations between India and the United States. Earlier this month, Washington announced it would lower tariffs on Indian goods after New Delhi agreed to halt imports of Russian oil — a shift that signals closer alignment on sanctions enforcement.

By tightening oversight of ship-to-ship transfers, India appears intent on preventing its waters from becoming a conduit for sanctioned energy trade, reinforcing its strategic positioning in a shifting geopolitical landscape.

Top stories

Finland Says Russia Building Cold War-Style Military Sites Near Border

Nuclear submarines in the Arctic. New bases near Finland. Europe’s northern flank is heating up.

Russia is reinforcing its nuclear and military infrastructure in the Arctic, including building new facilities near the Finnish border, Finland’s defence minister has warned.

Speaking on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference, Antti Häkkänen said Moscow is expanding its presence around the Kola Peninsula — a region that hosts much of Russia’s sea-based strategic nuclear arsenal and long-range aviation assets.

“Russia has most of their biggest strategic capabilities in nuclear, submarines, long-range bombers in the Kola Peninsula area,” Häkkänen said, adding that new facilities are being constructed along Finland’s border “same as the Cold War.”

The Kola Peninsula, spanning roughly 100,000 square kilometres, remains central to Russia’s Arctic posture. Finland, which joined NATO after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, has since emphasized strengthening deterrence in the High North.

Häkkänen welcomed NATO’s renewed focus on Arctic security, including the launch of Arctic Sentry, an enhanced vigilance activity aimed at boosting allied coordination in the region. Still, he suggested the Arctic should have been prioritized much earlier.

Finland has positioned itself as a key Arctic defence actor, with forces trained for extreme northern conditions. Helsinki recently secured approval for €1 billion in EU defence loans to strengthen land forces, including investments in armoured vehicles and drones.

While discussions in Europe have intensified about strengthening a continental nuclear deterrent — with France and the United Kingdom exploring broader coordination — Häkkänen stressed that U.S. support remains indispensable.

“In the short term, and even mid-term, we need the U.S.,” he said, describing Washington as “ironclad committed” to NATO’s Article 5 collective defence guarantee.

As Arctic competition intensifies and geopolitical tensions deepen, Finland’s warning underscores a broader shift: Europe’s northern frontier is once again a strategic fault line.

-

Minnesota2 months ago

Minnesota2 months agoFraud Allegations Close In on Somalia’s Top Diplomats

-

Middle East2 months ago

Middle East2 months agoTurkey’s Syria Radar Plan Triggers Israeli Red Lines

-

Editor's Pick2 months ago

Editor's Pick2 months agoWhy India Is Poised to Become the Next Major Power to Recognize Somaliland

-

ASSESSMENTS2 months ago

ASSESSMENTS2 months agoSomalia’s Risky Pact with Pakistan Sparks Regional Alarm

-

Analysis2 months ago

Analysis2 months agoTurkey’s Expanding Footprint in Somalia Draws Parliamentary Scrutiny

-

Analysis2 months ago

Analysis2 months agoRED SEA SHOCKER: TURKEY’S PROXY STATE RISES—AND ISRAEL IS WATCHING

-

Somaliland1 month ago

Somaliland1 month agoF-35s Over Hargeisa: The Night Somaliland’s Sovereignty Went Supersonic

-

Somalia2 months ago

Somalia2 months agoIs Somalia’s Oil the Price of Loyalty to Turkey? MP Blows Whistle on Explosive Oil Deal